When the television show “M*A*S*H” aired in the 1970s and 1980s, it was likely the first exposure for much of the American public to the use of military helicopter medevacs in combat. Set during the Korean War, the drama highlighted the lifesaving capabilities of the budding practice.

When the television show “M*A*S*H” aired in the 1970s and 1980s, it was likely the first exposure for much of the American public to the use of military helicopter medevacs in combat. Set during the Korean War, the drama highlighted the lifesaving capabilities of the budding practice.

Since then, medevac operations have evolved. The odds of surviving a critical injury improved from 75% in Vietnam to 98% in Afghanistan in 2011, with the average time getting to a stateside hospital also decreasing from 45 days to three, according to Army and Air Force medical reports.

As the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan wore on, the outcomes for seriously wounded warfighters continued to improve. The use of tourniquets, blood transfusions and pre-hospital transport within 60 minutes resulted in an about 44% reduction in deaths among critically injured casualties from 2001 to 2017, according to a study from the Journal of American Medical Association.

The importance of medevacs is exemplified when 2022 Disabled American Veteran of the Year Adam Alexander holds his infant daughter at his home in Wisconsin.

The Army veteran was firing on enemy positions in Afghanistan when he took a sniper round to the head. Medevac pilots were ordered not to land, but one didn’t get the order due to a technical error. The pilot landed, and Alexander is alive today as a result.

“I send a Christmas card to the flight medic who came to get me, every year,” Alexander said.

Alexander said medics inserted a tube to establish an airway during the flight from Firebase Chamkani to the hospital at Forward Operating Base Salerno, Afghanistan. Surgeons removed part of Alexander’s skull at Solerno, then he was flown to Germany where he was stabilized before being transported stateside to Walter Reed National Military Medical Center.

“Any other conflict, I can tell you that Adam would be deceased, and praise God and great medical technology he’s here today,” said Mike Hert, who served with Alexander in Afghanistan and is now a fellow member of DAV Chapter 17 in Oshkosh, Wisconsin.

As Alexander’s case confirms, these critically injured heroes often return, forever changed, to a country that has promised to care for them—making DAV’s mission even more necessary.

“Our country sends our fighting men and women into harm’s way, and many of them return with life-altering wounds,” said DAV National Commander Joe Parsetich, a service-connected disabled Air Force veteran of the Vietnam War. “Combat leaves those who uphold our freedoms with traumatic brain injuries, shrapnel wounds and limb loss in many instances. DAV stands with our wounded veterans to assist them with reaching their full potential and ensuring they receive the benefits they earned.”

Modern medevacs bring trained medics, equipment and speed from the battlefield to maximize the care administered in what is known as the “golden hour,” a crucial time when it is more likely a life can be saved.

Starting in Iraq, combat outposts were also equipped with medical bags that keep blood and IV fluids cool for immediate use on the battlefield. Today, combat medic specialist training starts with a 16-week program with extensive field training.

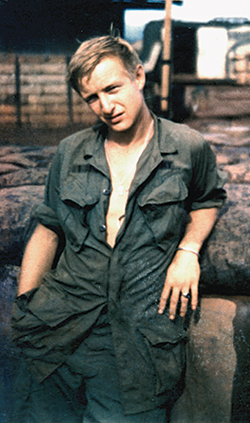

During the Vietnam War, DAV member David W. Chaffin, of Hebron, Kentucky, had 10 weeks of training as a medic before joining an air cavalry regiment. Chaffin said he received field training on the job.

“You wanted to stop the bleeding as much as possible,” Chaffin said.

His equipment consisted mainly of bandages, surgical scissors, a bottle of saline to start an IV and morphine.

There wasn’t always a stretcher in combat, Chaffin said, adding that the wounded often had to be carried to a helicopter landing zone in a poncho.

“I am sure the military is a lot more advanced today,” he said.

By the time of the invasion of Iraq in 2003, surgical units could fold out of the back of a Humvee, said Deputy National Service Director for Training Scott Hope, who served as a flight medic in Iraq for 17 months from 2003 to 2005.

Before wounded personnel made it to the medevac helicopter, medics on the ground could do things like apply a rapid tourniquet, which uses Velcro, or an occlusive dressing, which shields a chest wound from the open air while allowing breathing, Hope said. Aboard the aircraft, pumps could put more fluids into a patient than an IV drip. There were tools to increase oxygen and infuse blood with platelets during the flight to a hospital, he said.

“We would fly in hot and low,” Hope added.

For Alexander, the joy of marrying his wife and having a child was made possible because a helicopter pilot landed during combat, providing a lifeline for a critically wounded soldier.

“Every day above ground from here on out is a good day, because they gave me a 5% chance to live when I was injured, and here I am over 10 years later,” Alexander said.