Julius Boreali’s diary entry from May 29, 1944, is different from the more typical “calm sea, sun shining” entries that precede it:

12:30 am attacked by a group of German planes. They blew up a big oil depot. They tried to get it for 3 yrs and finally got it. Killed some American soldiers in barracks. We were at our guns but did no firing. We only hoped they could not see us in the darkness. One plane was shot down.

The attack was a sign of things to come. Boreali and his Coast Guard shipmates were docked in Falmouth, England, making preparations for the largest amphibious landing in history. In a matter of days, they would be starting the 170-mile journey across the English Channel toward Omaha Beach on the coast of Normandy, France.

The son of Italian immigrants, Boreali was born Dec. 15, 1922, and grew up in Howes Cave, New York. In 1942, there was a high potential to be drafted into the Army, so he decided to enlist in the Navy instead. But the day he went to Albany to sign up, the line to join stretched three blocks. He looked across the street and saw that no one was waiting outside the Coast Guard recruiting office. They took him on the spot, and three days later, he was at their training station in Manhattan Beach, New York.

Next was Wildwood, New Jersey, where he learned to be a baker. That’s also where he learned he would be stationed on a tank landing ship, commonly known as an LST. It was dangerous duty.

“You get on one of those, you’ll never come home,” Boreali recalled someone telling him.

LSTs were 300-foot-long, flat-bottomed ships designed specifically for amphibious landings. They could operate in shallow water, and their bows could open to offload vehicles, tanks and personnel from their giant cargo holds. Boreali said the ships looked like giant floating bathtubs.

Looks aside, LSTs would become a major part of the Allied forces’ ability to push into France and sustain operations to overthrow German forces and end the war in Europe. Boreali and the rest of the crew on LST-27 learned of their exact role when they read what was posted on the ship’s bulletin boards:

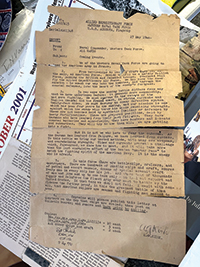

27 May 1944. SECRET From: Naval Commander, Western Task Force. To: ALL HANDS Subject: Coming events. We of the Western Naval Task Force are going to land the American Army in France.

Rear Adm. Alan Kirk’s message continued:

Every man in every ship has his job. And those tens of thousands of men and jobs add up to one task only—to land and support and supply and reinforce the finest Army ever sent to battle by the United States. In that task we shall not fail. I await with confidence the further proof, in this the greatest battle of them all, that American sailors are seamen and fighting men second to none.

A few days before D-Day, 300 men from the Army’s 29th Infantry Division and their equipment were loaded into Boreali’s LST. As they set sail, a priest gave everyone on board a benediction.

“They were trying to build up our morale,” he said.

Boreali detailed in his diary some of the horrors he witnessed on June 6, 1944, but the memories are vivid in his mind today, too.

“It was just getting daybreak. All of a sudden, these German [88 mm guns] and airplanes came overhead and started bombing,” he said. “Now that’s when fear set in. … There was no place to hide. You just had to stay where you were. I was on a 40 mm shooting at the airplanes.”

He didn’t sleep for the next three days.

“I was no cook anymore,” he said. “I was on a gun or out picking up the wounded on the beach.”

The conditions were brutal. Boreali said thousands of men were killed or wounded between the destruction inflicted by the German 88s, the mines in the water and soldiers drowning as they tried to wade ashore with 60-pound packs.

“They floated in to the beach that evening,” he said. “They just floated in. It was a mess.”

There were highlights and serendipitous moments in the midst of the horrors of battle, though, like one of the times Boreali went to shore to pick up wounded to bring them back to the ship.

“I reached down to pick up this one guy. He looked up at me and he said, ‘Julie?!’ I couldn’t believe it. It was Freddie Wessel, a kid I went to school with in Cobleskill,” Boreali said. “Thousands of men, and here he was. I picked him up and tears came to my eyes. You know, I still get tears in my eyes.”

Boreali brought Wessel back to the ship and to England. Not only had they gone to high school together, but their fathers both worked at the same cement plant back home.

“So when I got back to England, I wrote a letter to my father and mother. And I told them, I says, ‘Freddie Wessel, Whitey Wessel’s son, I just picked him up on the beach in France.’”

In his letter, he detailed that the bullet that hit Wessel went clean through and that he was safely recovering at a hospital in England. Boreali knew that families only received a telegram informing them their son was wounded in action with no other information provided.

When Boreali returned home a year later, the Wessels were the first people to come to visit him.

“They hugged me and thanked me because [that letter] put their minds at ease,” he said.

Over the months following D-Day, Boreali and the crew of LST-27 made dozens of trips from England to France to resupply and bring in reinforcements for the Army. There were no harbors to dock at, so it all had to be done at the beachhead.

“LSTs were the lifeline,” Boreali said. “Men, ammunition, food, material of all kinds—it was us. We brought it in.”

Boreali said there was imminent danger on each trip because of enemy acoustic and magnetic mines littering the channel. He witnessed many ships sink from these, but LST-27 kept bringing supplies.

“We had a job to do, and that was our job, and we knew it,” he said.

Nearly 80 years later, Boreali, sitting in his apartment in Schenectady, New York, carefully unfolds the D-Day message that was pinned to his ship’s bulletin board. It’s yellowed and worn with age. Clearly, the explicit instructions to destroy the message before sailing toward Normandy were never followed. Boreali had stuffed it into his seabag before anyone had a chance to burn it.

It’s now a piece of memorabilia he shares with his children, along with various magazine clippings and photographs.

“I was glad I did my duty,” said Boreali. “I felt that I did my job and did it well. I was important. They expected of me, and I gave it to them.”

Boreali, who recently turned 100, left service in 1946. He married, raised a family and became a life member of DAV Chapter 88 in Schenectady.

His daughter, Judy Sogoian, said that growing up, she and her siblings didn’t hear him talk much about his time in the military. And she admits, at the time, she never really cared about asking.

“But fortunately, when I started to care, my father was still here to give me the stories,” she said. “And I really appreciate that time that I have with him.”

Sogoian and her brother, Fred Boreali, have heard most of their father’s stories hundreds of times now. She likes the ones that don’t focus on the tragedy of war but on the humorous and touching moments.

One of her favorites is about how he despised having to make dozens of pies to feed the crew while the other baker got to make big sheet cakes that could be portioned out much easier.

“My father got this great idea: ‘If I didn’t have the pie tins, I wouldn’t have to be making pies,’” Sogoian said. “So in the middle of the night, he would go to the top of the ship … and he would start flinging off the pie tins. And the next day, when there were no pies, the head baker would say, ‘Where are the pies, Boreali?’ And he would say, ‘I had no pie tins. I don’t know what happened to them.’”

The head baker ordered more. But those “mysteriously” went missing, too. Eventually, the head baker stopped ordering pie tins. Boreali never got caught.

Sogoian said she loves those stories that illustrate the contrast between the gravity of the situation and the fact that her father and almost everyone else on board were still just teenagers.

Young, but in the words of Rear Adm. Kirk, “seamen and fighting men second to none.”

The last entry in Boreali’s diary spans June 9–12, 1945, when the crew of LST-27 arrived back in Falmouth. It was the same site where just over a year before, German planes attacked the base. All was quiet now. The war in Europe had ended a month earlier.

“We report to Falmouth,” he wrote. “At last we know we are going home.”

Even today, though, his thoughts go back to those who wouldn’t be joining him.

“Let me tell you something: I’m no hero,” Boreali said. “The heroes are all dead. They’re the ones buried over in Normandy. We came home.”