June 6, 1944, marked the first time George Mullins was ever in battle.

The day before, he boarded a Landing Ship, Tank (LST) to cross the English Channel to France as a replacement soldier with the Army’s 327th Glider Infantry Regiment supporting the 101st Airborne Division for Operation Overlord.

Mullins recalled that just before the troops loaded up, then-Maj. Gen. Maxwell Taylor, the commanding general of the 101st, jumped up on a table to make a speech.

“And that was, ‘Boys, this is it. At a certain time, we’re going to be on the beaches of Normandy,’” said Mullins. “That’s how I got the news [about D-Day].”

Six weeks earlier, more than 700 service members were killed during a secretive live-fire rehearsal of D-Day at Slapton Sands in Devon, England, known as Exercise Tiger. It was marred by German E-boat attacks, miscommunication and fratricide.

Mullins would’ve been at that exercise but checked into his unit just a few hours after soldiers had already departed for the training area. The base was a ghost town when he arrived.

So, with little training and even less understanding of what was about to happen, Mullins was sailing toward one of the largest combined military operations in history.

Operation Overlord was planned in secret over several years and brought the full spectrum of military power onto the beaches of Normandy. The intent was to drive the German forces out of France and create momentum for an Allied victory in Europe during World War II.

The operation’s success or failure fell largely on the shoulders of young men.

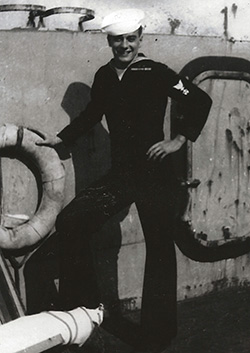

“We were all 19. We were all greenhorns,” said Richard Rung, a Navy veteran and D-Day survivor. “I didn’t know what end was up in regards to fighting like that.”

Rung’s assignment was as a diesel mechanic on the tank landing craft LCT-539, a vessel built in North Tonawanda, New York, only a few miles from where he grew up in Buffalo.

Like Mullins, he didn’t know what he was heading into. He’d been in England for a few months, unaware of the D-Day plans. On June 4, his skipper announced that they’d be leaving for France the next morning.

Rung’s LCT carried soldiers from the 1st Cavalry Division’s 161st Infantry Regiment and the 82nd Airborne’s 37th Combat Engineer Battalion. They all got seasick on the ride across the channel, he said.

Rung, who is a DAV member with Illinois Chapter 12, thought they were just dropping them off at Omaha Beach.

But at 7:30 a.m. June 6, when the front ramp of his LCT lowered, “it literally rained death,” he said.

His boat was hit immediately by two 88 mm and two 47 mm shells that killed two soldiers and wounded two others. He said some estimates put the volume of gunfire at Omaha Beach at 20,000 rounds per minute.

“I couldn’t believe the mess on the beach,” he said.

Meanwhile, to the west of Rung, Mullins was landing at Utah Beach. As an ammo bearer for a machine gun squad, his job was to take a cart loaded with boxes of .30-caliber rounds from the ship to the shore.

The flat topography of Utah Beach was a contrast to Omaha Beach’s cliffs, making the push onto land comparatively less dangerous and difficult, even while dragging a cartful of ammo. It was nothing like Omaha, Mullins said.

“They run them boys up against that cliff rock,” he said. “They had no place to go.”

D-Day was just the beginning for Mullins. He would go on to participate in the liberation of Carentan, Operation Market Garden in the Netherlands and the Battle of the Bulge in Belgium, earning a Bronze Star and Purple Heart along the way.

“Victory didn’t come cheap for no one,” Mullins said.

Late in the afternoon on D-Day, as Mullins made his way inland, Rung was aboard his LCT in the waters off Omaha Beach helping wash blood off the tank deck.

“I guess the hardest thing for me was the blood,” he said. “That was the most bothersome thing. I wasn’t used to that kind of blood.”

He and his crew beached their boat two days later. As Rung made his way onto land, what he witnessed seared into his memory.

“There were dead bodies in row after row, plus arms and legs collected without any other remains,” Rung said. “My question to my buddy was, ‘How do you identify a man if all you have is a leg or an arm?’”

Rung spent the next two months transporting troops, supplies and vehicles from the ships to the shore until the strategically important French port in Cherbourg could be taken back from the German forces and repaired.

His time in service wasn’t over, though. About six months after D-Day, he and his crew were sent to the Pacific to help on that front, too.

It’s been 80 years since D-Day, and the number of survivors still alive and able to give their firsthand accounts is dwindling. Though many were teenagers during battle, those who remain are near or past 100 years old.

But as the number of survivors fades, Rung, Mullins and other D-Day veterans have worked to make sure the history and personal stories live on. They represent the thousands who were killed that day, the tens of thousands who died in the Battle of Normandy, and the hundreds of thousands of men and women who are no longer with us but whose service played a role in the ultimate Allied victory in Europe.

With the help of his friend and caregiver, John Biancalana, Mullins wrote a book about his time in service. He especially wants people to know of the sacrifice made by those who died during Exercise Tiger. After service, Rung became a professor of history at Wheaton College in Illinois, and he has often publicly spoken about his experiences.

Through the battlefield return program of the Best Defense Foundation, both men have been back to Normandy on several occasions to participate in commemorative ceremonies, remember their fallen comrades and meet the descendants of the French citizens they helped liberate.

“I love the people there,” said Mullins. “They’re a people that appreciates freedom. … They understand it down to the little kids.”

The 80th anniversary of D-Day may possibly be the last milestone commemoration veterans of the Battle of Normandy will see in person. For those who’ve gone, the trips have reawakened some difficult memories but have also offered closure, healing and introspection.

“The first time I went back, all I could see is dead bodies, and they weren’t there,” Rung said as he recalled looking down at Omaha Beach decades removed from his time on LCT-539.

But on his most recent trip, he asked to be taken to the Normandy American Cemetery to quietly sit in the middle of all the crosses.

“I just wanted to be with all those guys that didn’t make it.”