Whether photos of the Civil War dead at Antietam, a shell-shocked soldier in a trench in Europe or Marines raising the flag atop Iwo Jima, the iconic images of every major American conflict have revealed both the horrors of combat and valor on the battlefield. For better or worse, war photography has always wielded an undeniable influence in the court of public opinion.

Whether photos of the Civil War dead at Antietam, a shell-shocked soldier in a trench in Europe or Marines raising the flag atop Iwo Jima, the iconic images of every major American conflict have revealed both the horrors of combat and valor on the battlefield. For better or worse, war photography has always wielded an undeniable influence in the court of public opinion.

That power grew exponentially during Vietnam, when the proliferation of television allowed such images to reach into homes on nightly newscasts nationwide. Photos of the My Lai massacre and of a young Vietnamese girl running naked through the street as napalm melted away her skin began to sway public opinion against the war.

“Those guys came home to people spitting on them and calling them baby killers,” said Chris, a Marine Corps veteran of Afghanistan who requested anonymity due to concerns surrounding his current employment. “That’s totally foreign to me. And to be quite honest, it always made me feel like there was a difference between us and them. Kind of like we fought the good war and they fought the bad one. Because everyone was behind us after 9/11.”

Chris attributed that disconnect to growing up hearing from family members about how “we lost Vietnam,” which he thought was supported by the famous image of an American helicopter evacuating diplomatic staff from the rooftop of the U.S. Embassy in Saigon in April 1975.

But he knows a single picture doesn’t tell an entire story and admitted that, before he joined the military, he never sought out any Vietnam veterans to get their take on the war they served in. That changed last summer when the image of a Chinook helicopter hovering above the U.S. Embassy in Kabul made its rounds on social media.

“I saw that and thought to myself, ‘Afghanistan is my Vietnam now,’” he said. “And that hit me like a ton of bricks. But it also made me feel far more connected to those guys than I had ever felt before.”

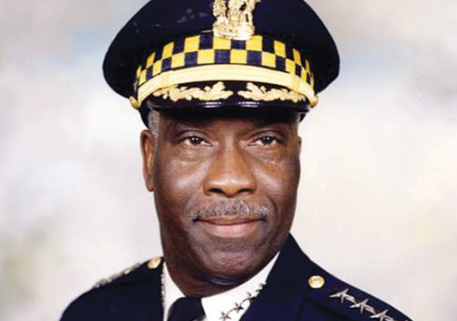

DAV National Commander Andy Marshall is one of those Vietnam veterans. Twice wounded in combat, the Army veteran said he also felt dismayed when he witnessed what unfolded in Afghanistan.

“I couldn’t believe they’re doing this again to our troops,” he said. “It was pretty depressing to see it happen 50 years later.”

“I feel like something that ties Vietnam and Afghanistan veterans together is all the negative and conflicting feelings one can have after their country pulls out from a war they were in,” said Carmen McGinnis, a Marine Corps veteran of Afghanistan who now serves as a DAV national area supervisor. “But I don’t make the big decisions and can’t dwell on whether I agree or disagree.”

While each generation has its own unique traits, Marshall said, the military experience—especially that of a war zone—is a unifying thread. Veterans share a distinctive connection, something DAV has seen passed down from its members beginning with those who fought during World War I.

“You’re there because you were sent there to do your job,” he said. “And you just hope your family and the American public appreciate it.”

Marshall did note, however, that some of the most heartwarming thanks he ever received from his service came from the post-9/11 generation.

“I heard things I never heard before because of Iraq and Afghanistan veterans,” he said. “They’ve always shown me a genuine gratitude for our sacrifices, because they know we weren’t treated the way we should’ve been when we returned home. There are no words that can adequately describe my appreciation for that.”

For Marshall, Chris and McGinnis, one strong connection they all share is that they don’t look back at their time in uniform with regret.

“I know I was there for a reason,” said Marshall. “If I had not gone into the military, my life would be so unbelievably different. It changed it for the far better.”

For his part, Chris echoed the sentiment.

“I gave the military some of the best years of my life, and it gave me some of the best experiences in return,” he said.

“And although it wasn’t the end any of us wanted, we did make a difference over there,” Chris added. “There’s an entire generation of Afghans who got to live in a way they otherwise might not have if we didn’t help out. But what good is that if it can’t be maintained for the next generation? I guess that’s what I’ve been wrestling with, and I’m not sure I’ll ever find the right answer.”

“What continues for us is the war inside ourselves, and that’s a war we can all win,” said McGinnis. “What I focus on is taking care of my mental health and that of my fellow veterans, however I can, and on the good I know occurred for the people of Afghanistan.”

Marshall saw many of his fellow Vietnam veterans struggle to cope with the emotional wounds of war during his four decades as a national service officer. Similar to Chris, they wrestled with the meaning of the sacrifices they and others made on the battlefield.

“I know all too well the range of emotions that veterans of Afghanistan have been feeling lately,” said Marshall. “My biggest concern, though, is that their emotions and attitudes toward how things ended over there could negatively affect their mental health. More than anything, I want them to know that their service and sacrifice matters, and no picture can ever change that.”