July marks 60 years since the Civil Rights Act became law, ending legalized racial segregation in the United States.

It was a major milestone for social justice and an outcome championed by well-known activists including the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. and Rosa Parks. Lesser known, though, is the movement’s connection to Black veterans of World War II who suffered mistreatment and the many who broke barriers on multiple fronts in uniform.

Their service overseas, particularly those who served in World War II, was a catalyst for the fight for equality when they returned home.

“There’s no way you could go through all that … and come back and then just go right back to sitting in the back of the bus and not think anything of it,” said Yvonne Latty, author of “We Were There: Voices of African American Veterans, From World War II to the War in Iraq.” “To me, they were the leaders of the Civil Rights Movement, whether in big or small ways in their communities.”

Before World War II, Black service members were limited in what jobs they could perform in the military, often relegated to stateside duties or menial support roles, such as stewards. But as the war progressed, high casualties and the need for more people to fight opened up more opportunities for Black service members.

“I don’t think that they could continue having a robust Army and discriminate,” said Latty.

Black service members served with distinction. Historical accounts from deployed segregated units, including the Tuskegee Airmen, the 761st Tank Battalion (Black Panthers) and the 6888th Central Postal Directory Battalion (Six Triple Eight), reveal stories of bravery, sacrifice and determination.

“Everybody wanted to do their part,” said Edna Cummings, an expert on the Six Triple Eight and a retired Army colonel. “They were patriots. They loved their country.”

The Six Triple Eight was an all-Black female unit that deployed to England in 1945, tasked with processing millions of pieces of backlogged mail accumulated over years. While in Birmingham, England, they were given six months to finish but cleared several hangars full of mail in just three months. (The January/February 2024 edition of DAV Magazine has an in-depth article about their achievements.)

Their motto was “no mail, low morale,” but they knew they were serving for a greater purpose. Cummings said that before the unit deployed, Mary McLeod Bethune, a civil rights leader who advocated for Black women to be able to serve in the Women’s Army Corps, sent a telegram telling them that they represented 15 million Black citizens, to carve a niche for themselves and to do well.

Like other Black veterans at the time, their military experience empowered and equipped them to get involved in the Civil Rights Movement when they came home, said Cummings, who is a member of DAV Chapter 33 in Fort Meade, Maryland.

“One thing the military teaches you is how to task organize, manage and lead under harsh conditions,” she said.

The distinguished service of Black service members during the war was part of the reason that President Harry Truman signed an executive order integrating the military in July 1948.

It was a positive step forward, but it also created a dichotomy for many Black people who served in the military during that time, especially those who were stationed in the segregated South.

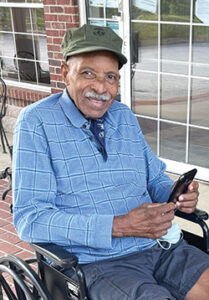

DAV member Tony Prince of Chapter 55 in Porterdale, Georgia, recalls his father Stacey’s experiences when he enlisted in the Marine Corps in 1956. He was with field artillery during his two-year enlistment and was stationed at Camp Lejeune, North Carolina. On duty, racial discrimination wasn’t much of a factor, he said.

“They were just giving everybody hell,” said Prince. “That was the nature of the training as a Marine during that era.”

But after hours and off base, things were different. Prince said his father and other Black members of his unit would keep to themselves in the barracks, always traveled off base in groups of two or more, and were careful to avoid certain places.

“Your being in uniform and on leave didn’t necessarily mean you were immune to racial stuff and what was going on,” said Prince.

Unequal treatment continued after Prince’s father left military service in 1958, such as when he and his wife had difficulty renting a home in Washington, D.C. However, because of his service and the service of others in the integrated force—everyone together in uniform regardless of background—the cultural tide was beginning to shift.

“It was impossible to make society go back to what it was before the military was integrated,” said Prince.

He said the passing of the Civil Rights Act in 1964 was the final bit of muscle needed to push back against those who opposed change.

Prince, like his father, played football in high school. He went on to play at Howard University in Washington, D.C., and was a part of its Army ROTC. He received his commission as a second lieutenant in the Army in 1982.

Stacey Prince, who died in 2023, had never seen a Black officer during his time in service.

“When I first got commissioned, and he pinned my lieutenant bars on me, I said, ‘Hopefully, Dad, being an officer makes up for not being a Marine,’” Prince recalled. “He said, ‘It does. I’m proud of you. I’m so proud of you.’”

Prince’s military experience was vastly different than his father’s.

“I have never seen, when I was in and after, that it has ever mattered what your race, ethnicity or what part of country you were from,” he said. “And I believe that’s from earlier generations and what all they had to go through and put up with both in the service and when they got out.”

Cummings, who grew up in Fayetteville, North Carolina, also came from a military family. She saw service as a practical career step and, in 1974, was the first Black woman to receive a commission in the Army from Appalachian State University’s ROTC program.

“I know when I came in, my generation were considered pioneers,” she said. “But there were pioneers before us that no one ever talked about and no one ever used to motivate us.”

She spent 25 years in the military never hearing about the Six Triple Eight, only learning about the battalion after she retired.

Since then, she has used its story as a way to inspire the next generation of Black women in the military and as a way to bring the many untold historical accomplishments of Black service members to light. Her efforts were a large reason the Six Triple Eight received the Congressional Gold Medal from President Joe Biden in 2022.

Latty, who talked with more than two dozen Black veterans for her book, said a common theme in her conversations was pride of service and sacrifice, even in the face of adversity.

“And through their sacrifices, I think that they made this country better, and I think they made things better for their people,” she said. “And I think it’s up to us now to take advantage of the things that they have done, the doors that they opened for us.”