Leading up to DAV’s 100th anniversary in 2020, DAV Magazine continues to chronicle each decade in our organization’s history and service in the military. From Afghanistan to Iraq and everything between, this installment provides historical background and highlights of important issues and events that affected service members, disabled veterans and their families during the first 10 years of the 2000s.

At the turn of the 21st century, the United States was at peace.

The Gulf War had ended nearly a decade earlier, and America’s military trained for threats that seemed abstract and distant. But on Sept. 11, 2001, war hit home. The nation stood witness to the most deadly terrorist attack on U.S. soil, as nearly 3,000 people were killed when hijacked planes crashed into the Pentagon, the World Trade Center towers and an open field in western Pennsylvania.

“This is a day when all Americans from every walk of life unite in our resolve for justice and peace,” said then-President George W. Bush in an address following the attacks. “None of us will ever forget this day. Yet, we go forward to defend freedom and all that is good and just in our world.”

DAV members jumped into action. In Florida, a DAV Transportation Network van helped transport blood shipments to victims in New York. A mobile service office delivered thousands of articles of clothing and comfort kits to first responders at the Twin Towers. Service officers unable to return to their New York City office began volunteering at Giants Stadium and the World Trade Center ruins, and set up a makeshift shop on Pier 95 to enable DAV to provide aid and identify impacted veterans and their families.

Meanwhile, President Bush vowed to track down the 9/11 architects—namely Osama bin Laden—remarking that “we will make no distinction between the terrorists who committed these acts and those who harbor them.” On Oct. 7, 2001, the U.S. led a coalition invasion of Afghanistan, with plans to dismantle al-Qaeda and the Taliban government that was sheltering bin Laden.

Less than two years later, U.S. military members found themselves at the helm of yet another coalition invasion, this time in Iraq. As the country engaged in wars on two fronts, DAV began to focus on the influx of veterans who would be returning home and the signature injuries that would follow.

Jose Herrera served in the Marine Corps from 2006 to 2011. After a deployment to Iraq, Herrera believed he was returning again, but new orders redirected him to Afghanistan. In what would be the largest airlift insertion of Marines since Vietnam, Herrera was among the 4,000 Marines in Helmand Province launching Operation Khanjar, aimed at driving the Taliban out of southern Afghanistan.

Improvised explosive devices were a constant threat—Herrera estimated his unit unearthed 19 each week—but it was enemy fire that claimed the life of his good friend Pfc. Donald “Wayne” Vincent in July 2009.

“I fought because of the guy next to me,” said Herrera, a life member of DAV Chapter 11 in Wilmington, N.C. “It’s about a camaraderie; this entire generation understands that to the core.”

Amy Bahl, a combat medic in the Army National Guard, was deployed shortly after the invasion of Iraq. The then-25-year-old spent a year in Mosul treating gunshot wounds and injuries sustained from roadside bombs and IEDs.

“My day-to-day life was very little sleep, followed by trying to fix and save as many people as we possibly could,” recalled Bahl. “It was really hard because medics take a lot of things personal. We always felt guilty when we couldn’t save somebody.”

While weaponry was becoming increasingly lethal, better training and medical advances meant surviving multiple severe injuries was the norm, not the exception. In 2016, Army Lt. Gen. Nadja Y. West, surgeon general of the Army, said that 92 percent of soldiers wounded in Iraq and Afghanistan made it home alive, compared to 75 percent during Vietnam.

So-called “invisible wounds,” however, aren’t as easy to triage on the battlefield. Traumatic brain injury (TBI) has been referred to as the signature injury of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, with nearly 350,000 diagnoses of TBI in the military since 2000. And like those who served in earlier conflicts, veterans of Iraq and Afghanistan experienced post-traumatic stress—with 13.5 percent of those who deployed screening positive.

Other conditions—cancers as well as neurological, gastrointestinal and respiratory illnesses—developed over time, resulting from exposure to the burn pits commonly used to get rid of waste at military sites in Iraq and Afghanistan. Many veterans returned home and then grew ill—some even died—after contact with the dangerous toxins. In 2008, DAV began advocating to bring to light the health risks associated with burn pits, ultimately helping establish the burn pit registry for veterans who served in Afghanistan and Iraq as well as Djibouti, Africa.

DAV National Senior Vice Commander Stephen “Butch” Whitehead’s Minnesota National Guard unit received orders to Iraq in 2005. After 15 months in theater performing security and detainee operations, he returned home to a new assignment—helping soldiers transitioning out of the military—which is how he first came to know DAV.

“The mission aligned with my passion for serving those who served, so it was a natural fit,” explained Whitehead, who retired as a command sergeant major earlier this year after 27 years of service. “DAV truly stands ready to fight for veterans and their benefits.”

While Operation Iraqi Freedom officially ended in 2011, American troops returned again in 2014 in response to terrorist activity from the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant. Operation Enduring Freedom in Afghanistan ended in 2014, but an advisory mission began in 2015. American troops are still in both Iraq and Afghanistan.

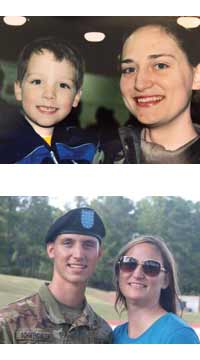

Bahl echoed the sentiment that she hears fellow post-9/11 veterans share: They served overseas so that the next generation wouldn’t have to. Despite this, Bahl’s oldest son, Austin Schwendinger, who was 5 when she deployed, joined the National Guard in 2016.

That same year, Bahl joined DAV. She currently serves as senior vice commander for DAV Department of Iowa as well as commander of DAV Chapter 6 in Dubuque.

“DAV helped me with my claim,” explained Bahl. “They fought for me so I wasn’t by myself. So I figured, if someone is going to help me, why not join the fight?”