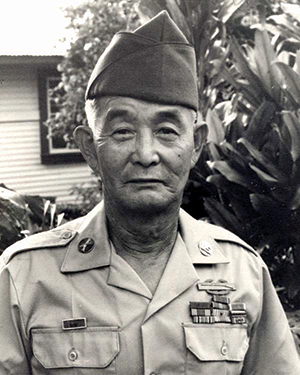

Brian Moto’s late father, World War II veteran Kaoru Moto, didn’t talk about the war in front of his children, and Brian and his siblings knew better than to ask.

Instead, they learned bits and pieces of their father’s story from other veterans and members of the local DAV chapter in Maui, where Kaoru Moto was a lifetime member.

“And they would say, ‘Oh, your father was a very brave man,” Brian Moto remembered.

The citation for the Distinguished Service Cross awarded to his father told more of the story. Over the years, Brian would read many accounts detailing his father’s heroic actions on July 7, 1944, near Castellina, Italy.

That day, Kaoru Moto was the scout leading his platoon to higher ground. After he spotted a machine gun nest, Moto killed one German gunner and captured another. Taking his prisoner with him, Moto took cover at a house a few yards away.

He soon realized he was surrounded by Germans and engaged them with fire, forcing most of them to withdraw. Then a single remaining sniper fired at Moto and struck his left leg, severely wounding him.

Moto bandaged his wound and moved to the rear for treatment. Injured and bleeding, he spotted another enemy gun nest and opened fire, wounding two of three enemy soldiers and forcing them to surrender.

For his actions, Moto was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross, Purple Heart, Bronze Star and Italy’s War Cross of Military Valor.

“I would hear this repeated over my childhood,” Brian Moto said. “Someone would say something like, ‘Oh, you know, your dad should have gotten the Medal of Honor, but he didn’t because he was Japanese, and they didn’t give Medals of Honor to Japanese Americans [during World War II].’”

After the deadly attack on Pearl Harbor by Japanese forces on Dec. 7, 1941, Americans of Japanese ancestry were eyed with suspicion and became targets of discrimination. Over the next few years, roughly 120,000 people of Japanese descent were incarcerated in camps in the U.S.

Before 1941, Kaoru Moto was drafted into the Hawaii Territorial Guard. After Pearl Harbor, he became part of the 100th Infantry Battalion, a unit composed mostly of second-generation Japanese Americans, or Nisei, many of whom were from Hawaii.

“The United States Army wasn’t sure what to do with these men, where to send them,” Brian Moto said. “They weren’t sure if they would make good fighters—or if they would fight.”

In spite of their families’ incarceration, the soldiers of the 100th fought. The battalion, which later merged with the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, became the most decorated unit of its size and length of service in military history and received three Presidential Unit Citations, according to the 100th Infantry Battalion Veterans organization. Its soldiers became synonymous with bravery.

“Hawaii is a place that fostered … cohesion, a sense of loyalty, a sense of love and affection, and caring,” Brian said. “The Hawaiian culture and traditions did shape them and, I think, helped to contribute to their service. It helped to make them brave and helped them to give a sense of purpose and mission.”

Still, it took decades for Kaoru Moto and others of the 100th to get the recognition many agreed they deserved. In mid-2000, Moto’s Distinguished Service Cross, along with those of 20 other Japanese American soldiers, was upgraded to the Medal of Honor.

Alongside his mother and siblings, Brian Moto traveled to Washington, D.C., for an elaborate, multiday series of events ending with a formal ceremony on June 21 at the White House, led by then-President Bill Clinton. Today, Kaoru Moto’s Medal of Honor is displayed in an exhibit, “Nisei Soldier Experience,” at the National Museum of the United States Army.

After Kaoru Moto returned from war, he met and married Violet Saito and the two had five children. Having grown up poor in the sugar camps of Maui and unable to get more than a grade school education, Kaoru Moto yearned for his children to go to college. Brian fulfilled his father’s dream thanks in part to a DAV scholarship he earned as a youth volunteer. “I can say that the DAV helped to shape my life and career,” Brian said. “And for that I’m very appreciative.”

Brian happily displayed that appreciation last year when he signed documents naming DAV as a beneficiary of his estate. It was his way of thanking the organization that provided his family support and community for so many years. His generosity also helps preserve the legacy of his father and others like him.

“My dad’s story is not just a family story, but it sort of has a broader symbolic significance,” Brian said. “It’s really an American story. It’s very much something that I think that all Americans can be inspired by and be proud of, regardless of your background or where you’re from.”