“Semper Fi,” Carlo Melone called out to the guy in front of him in line at a Chicago pharmacy. Melone knew he was saying hi to a fellow Marine veteran from the hat and patches on the man’s jacket.

Semper Fi is short for the Marine Corps motto, “Semper Fidelis,” which means “always faithful” in Latin. It’s a common greeting between Marines, past and present. But when Melone, a DAV benefits advocate, said it to Jose Rosales, it was more than a hello. It was a chance introduction that would wind up changing Rosales’ life.

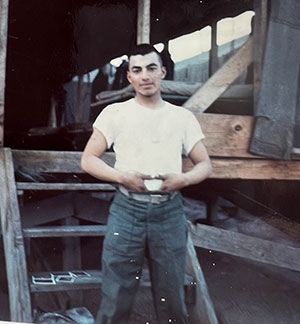

Rosales had dropped out of high school in 1969 to enlist in the Marines at 17. He was inspired by his cousin, Pete Lopez, who had joined a year before, went to Vietnam and was wounded in action.

Soon, Rosales was in Vietnam himself, running missions to secure drop zone perimeters.

He made it out of Vietnam seemingly without injury, thinking little of the planes that had flown overhead, spreading the tactical herbicide Agent Orange around him. He said that his eyes would get watery after the planes passed, but he didn’t think much more about it at the time.

After his time in Vietnam, he returned to the states, was discharged in 1971, got married in 1972 and went to work doing metal plating for the airline industry.

Then in 1978, doctors diagnosed Rosales with Type 2 diabetes. They never linked the diagnosis to any cause—Agent Orange exposure, lifestyle or otherwise.

He said they just told him he had diabetes and prescribed him insulin. He had to adjust to a new normal of regularly monitoring his glucose and taking insulin shots up to four times a day.

“You just try to do the best you can, because if you let it get to you, you’re going to break down,” said Rosales.

For the next 40 years, he relied on his medical insurance to partially cover his treatment costs. The balance had to come out of pocket, so sometimes he would have to go without his medication.

“Insulin was costing me almost $300 a month,” said Rosales. “I couldn’t afford that.”

No one had told him that, since 2001, the Department of Veterans Affairs has recognized a presumptive connection between Agent Orange exposure and Type 2 diabetes. That is, until he met Melone in line at the pharmacy on that cold winter morning in 2019.

“If I had hit one more red light or there was a person between us in line, he would not have known this connection,” said Melone. “It was one of those random encounters that every service officer experiences when we get out in our communities.”

Even with this new information, Rosales said he was hesitant at first about Melone’s offer to help him file a claim. His mind kept going to the others around him in Vietnam who he felt had suffered worse injuries and disabilities.

But after talking with Melone more, Rosales made the decision to file the claim 11 months after he first submitted his intent to file with the VA.

Then in 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic hit, slowing the claim adjudication process.

Despite the delays, Rosales persisted. After waiting almost a year to be seen by the Veterans Health Administration for his compensation and pension exam, he received his rating decision in March 2021.

He said a huge weight was lifted off his shoulders. Before, not only was he paying out of pocket for his own medication, but he was also trying to pay for his wife Debbie’s cancer treatments. The VA decision meant he no longer had to worry about affording insulin.

“Now I get it through the VA, and that helps me a lot,” said Rosales, now a DAV life member with Chapter 42 in Hanover Park, Illinois.

The decision allowed Rosales to have the peace of mind he hadn’t had before, but Melone’s job wasn’t done. As he reviewed the rating decision, he noticed the effective date was wrong. It was listed as the claim submission date, not the intent to file date—an 11-month difference. Melone also learned that Rosales’ wife had died 19 months into the adjudication process, but Rosales was paid as someone who was single with no dependents the entire time.

Melone worked to fix the two errors. He said the attention to detail and effort he puts into every claim stems from his view that being a benefits advocate is like being on another tour of duty. The difference is that now his service focuses on changing the lives of fellow veterans.

“I’m very proud of being a retired Marine, albeit medical. However, as a senior national service officer, I’ve spent the last 12 years literally changing the lives of the men and women of all branches of service in our country,” Melone said. “It’s such an incredible feeling to be able to do that.”

For Rosales, the decision doesn’t take away his diabetes diagnosis. He still has to take daily insulin shots and monitor his glucose. He couples this with staying active by regularly golfing, bowling, playing softball and weightlifting. But the decision affords him the opportunity to not worry about how to pay for treatments for a disease he developed from serving his country.

Rosales said his advice to other veterans is simple: “Call DAV—they’ll help you.