How World War I veterans took the fight to Washington and lit the fuse for the future of advocacy

In 1924, four years after the founding of the Disabled American Veterans of the World War (DAVWW)—now DAV—and six years after the end of World War I, the U.S. government promised war veterans a bonus for their service. The catch, however, was that the bonuses would not be allocated for nearly two decades.

The law determined that any veteran who had served in the armed forces during the Great War was due compensation at the rate of $1 a day for domestic service and $1.25 for each day spent overseas. Those entitled to $50 or less were to be paid immediately; the rest were to receive certificates they could redeem on their birthdays in 1945. If veterans passed away before they had the chance to redeem their certificate, the bonus would be awarded to their estate.

But in 1929, disaster hit when the stock market crashed, causing a downward spiral of economic collapse that adversely affected the world economy. The Great Depression that followed left more than 15 million Americans jobless and desperate for income. By 1932, nearly a quarter of all Americans were out of a job, and the Depression was still dragging on with no end in sight. Many veterans, facing the same plight as the rest of the country—and many also living with wartime injuries and illnesses—began to call for the government to award the bonus certificates early to help ease some of the financial burden.

Walter Waters—who served in the Army during the war—began to rally his fellow veterans in Portland, Ore., with a plan to board a train and travel nearly 3,000 miles to the nation’s capital to demand what they were promised. In May 1932, Waters and a number of unemployed World War I veterans organized a group they called the Bonus Expeditionary Forces—or Bonus Army—to march in Washington, D.C. Inspired by the Portland group, other Bonus Army units formed in communities across the country. Radio stations and local newspapers carried accounts of the growing army headed for the nation’s capital.

“We had no money, but perhaps a group, whose only support was in its numbers, might go to Congress and make some impression,” Waters recalled in the book “B.E.F.: The Whole Story of the Bonus Army.”

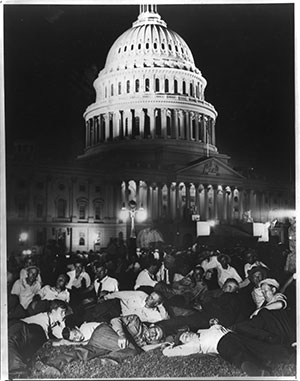

By June, thousands of veterans set up camp in Washington within view of the Capitol. With few resources, they set up a shantytown on the Anacostia Flats—located across the Anacostia River from the Washington Navy Yard and a few short miles from where DAV’s National Service and Legislative Headquarters is today—vowing to stay until Congress passed a bill providing full and immediate payment of their bonus certificates.

“Outside of the Capitol was a new argument for immediate payment of the bonus—eight thousand men, sitting on the steps, the lawns, the curbstones,” Waters said in his account. “The Senators were experiencing a new type of lobbying, not that of being entertained in some swank hotel where the business at hand is nonchalantly mentioned after a few drinks have been served, but that of being shown something of the poverty that had prompted the demand for the immediate payment of the bonus.”

President Herbert Hoover refused to address the veterans, though a congressional delegation did agree to hear them out.

“The proposal is to authorize loans upon these certificates up to 50% of their face value,” Hoover wrote in a letter to Sen. Reed Smoot of Utah. “As the face value is about $3,423,000,000, loans at 50% thus create a potential liability for the government of about $1,172,000,000, and, less the loans made under the original Act, the total cash which might be required to be raised by the Treasury is about $1,280,000,000 if all should apply.”

Soon, a debate began in Congress over whether to meet the veterans’ demands.

Rep. Wright Patman—also a World War I veteran—took up the veterans’ cause and resurrected a bill he had introduced three years earlier that had fallen flat. The Patman bill would immediately provide bonus payments to eligible veterans.

By June 13, Patman’s cash-now bonus bill, authorizing an appropriation of $2.4 billion, had made it out of committee and was headed toward a vote. On June 14, the legislation, which mandated the immediate exchange of bonus certificates for cash, came to the floor. The following day, the House of Representatives passed the bonus bill by a 211–176 vote.

More than 8,000 veterans—many of them members of the DAVWW—gathered in front of the Capitol on June 17 in anticipation of the Senate vote. Ultimately, the bill was defeated in the Senate, but many in the Bonus Army did not pack up and go home. About 10,000 people stayed in the shantytown, refusing to give up the fight. Seemingly, they maintained a peaceful and unarmed occupation.

However, there was a growing belief by Hoover that the veterans posed a threat to national security. On July 28, Attorney General William Mitchell ordered local police to remove the protesters. When police arrived to move them out, a riot erupted and police shot and killed two men. The Army—led by Gen. Douglas MacArthur—was called in to forcibly evict the Bonus Army from their makeshift camps.

According to Smithsonian Magazine, “MacArthur ordered his men to clear the downtown of veterans, their numbers estimated at around 8,000, and spectators who had been drawn to the scene by radio reports.”

The people in the camp were driven off by the cavalry with tanks and tear gas. MacArthur ordered his troops to set fire to the shanty settlements and the veterans’ belongings. Hospitals were overwhelmed with the wounded.

“Flames rose high over the desolate Anacostia Flats at midnight tonight,” The New York Times reported. “A pitiful stream of refugee veterans of the World War walked out of their home of the past two months, going they knew not where.”

“These ex-servicemen could not know, as they felt the hard city streets through their thin-soled shoes, that there were to bring to a wearied Administration its most crucial problem in four years of dilemmas,” read Waters’ account.

Indeed, the incident reflected poorly on Hoover, who lost the 1932 election to Franklin D. Roosevelt.

In 1933, three months into Roosevelt’s first term, a second, smaller Bonus March was defused with promises instead of military action. Roosevelt provided the marchers with a campsite and three meals a day. He also offered them work in the Civilian Conservation Corps, a New Deal public works program, waiving the age limit set for civilians.

In 1936, Patman reintroduced the cash-now bonus act—the Adjusted Compensation Payment Act of 1936—which finally became law, authorizing the immediate payment of the World War I bonuses. The first veterans began cashing checks in June of that year.

“DAV was founded by this generation who saw firsthand what could be done when they banded together to demand the government take care of its nation’s wartime disabled veterans,” said Washington Headquarters Executive Director Randy Reese. “The Bonus Army March of 1932, which included approximately 20% disabled veterans, is a reminder to us all of the great sacrifice they made during the war—and continued to make in order to fight for veterans of all generations.

“We would not be here today as an organization, or with the services and benefits we’ve earned, without their sacrifice and determination. As we move into our second century of service to veterans, we must remember those who came before us and continue our advocacy on behalf of the men and women who served.”