World War II hero and DAV life member honored in documentary

It was Jan. 16, 1942, and Japanese enemy fire was raining down on the U.S. Army’s 26th Cavalry Regiment in the Philippines. Ed Ramsey, then a 24-year-old lieutenant, glanced at his mounted troops then back toward the enemy. Without time to consider whether his men were outnumbered, he used hand-and-arm signals to issue the command—Charge!—beginning the last recorded wartime horse cavalry charge in U.S. history.

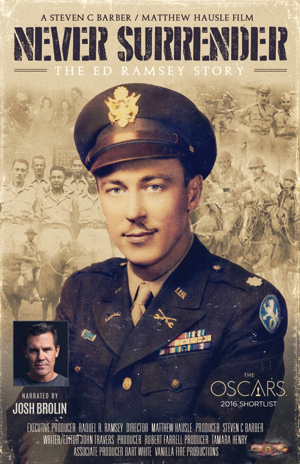

Lt. Col. Ramsey, who passed away in 2013, may be among the Army’s most forgotten warrior-leaders of World War II. But a recent documentary, “Never Surrender: The Ed Ramsey Story,” highlights the significant role and impact the DAV life member had on the war in the Philippines.

Ramsey was born in 1917 in Illinois but spent much of his youth in Kansas before graduating from the Oklahoma Military Academy. He entered active service in February 1941 with the renowned 11th Cavalry Regiment in California.

While attending the Oklahoma Military Academy, Ramsey developed a love for polo, which ultimately prompted his voluntary service in the Philippines with the 26th Cavalry Regiment in June 1941.

“The 26th had an excellent polo club, something the 11th Cavalry stateside lacked,” Ramsey said during a 2008 interview.

After Japan attacked Pearl Harbor and invaded the Philippines, Ramsey’s regiment was ordered north to oppose the enemy landings in Lingayen Gulf.

However, on the morning of Jan. 16, 1942, Maj. Gen. Jonathan Wainwright, the North Luzon Force commander (and future DAV national commander), saw the lieutenant, whom he recognized from the 26th Cavalry’s polo matches. He ordered Ramsey to take the advance guard into Morong.

Ramsey led three mounted units—a 27-man advance guard of Philippine Scouts, the 26th Cavalry and the 1st Regular Division of the Philippine Army—into the jungle. Encountering a Japanese infantry and artillery force, he ordered the historic cavalry charge. After a bitter battle in which they sustained only three casualties, his troops repelled the Japanese force and held Morong.

For gallantry in action, Ramsey received the Silver Star. More honors followed, including a Purple Heart and three Presidential Unit Citations for defense of the Philippines, Lingayen Gulf and Bataan.

The success of the charge was short lived, however. Bataan eventually fell to the Japanese. Ramsey escaped capture and the infamous Bataan Death March by heading into the jungle to join Lt. Col. Claude Thorpe, who had been sent by Gen. Douglas MacArthur to establish a resistance movement among the Philippine natives.

They trained without uniforms and with very few weapons, suffering under dire conditions. At one point, Ramsey underwent surgery to remove his appendix without anesthesia.

As the resistance forces grew in effectiveness and number, reaching 40,000, so did their risk of capture and torture by the Japanese. After three years and as the U.S. invasion neared, Ramsey, by then a major, was the only officer remaining. He established radio contact with MacArthur, who ordered him to step up the information gathering and disruption of the Japanese forces. On Jan. 9, 1945, MacArthur’s forces arrived at Lingayen Gulf. And Ramsey, the guerilla war fighter whom everyone—including his family—thought was dead, was back with the U.S. Army.

MacArthur credited Ramsey’s actions with saving tens of thousands of American and Filipino lives and personally pinned the Distinguished Service Cross on the newly promoted lieutenant colonel. Ramsey was then sent home; he weighed just 90 pounds.

A hero to the Philippine people, Ramsey was awarded the country’s Medal of Honor, the Philippine Distinguished Conduct Star, the Distinguished Service Star with Oak Leaf Cluster, the Gold Cross of Valor and the Wounded Personnel Medal.

“When I think of leaders and people who are courageous and dedicated themselves to the United States Army and our country, I think of Ed Ramsey,” said retired Army Lt. Gen. Bob Wilson, who attended the film’s premiere. “Ed Ramsey gave more of himself to this country than most ever will.”

After the war, Ramsey returned to Oklahoma University and graduated from law school in 1952. He started his own consulting firm in Taiwan and the Philippines before retiring to California in the 1990s.

In 1991, Ramsey coauthored a memoir, “Lieutenant Ramsey’s War: From Horse Soldier to Guerilla Commander,” and testified before Congress on three different occasions on behalf of Filipinos who had fought for the U.S. during World War II. On Nov. 30, 2016, Congress officially granted national recognition to the Filipino soldiers who served under the United States Army Forces of the Far East during World War II.

“Ed Ramsey is the epitome of a warrior and what it means to be a DAV member,” said National Membership Director Douglas K. Wells Jr. “He not only fought valiantly and without fear, but he never stopped fighting. When the war was over, he remembered the Filipinos he fought side by side with and continued to fight for their promised benefits. He’s a true DAV legend.”

Ramsey’s widow Raquel Ramsey was heavily involved in the filming of the documentary.

“God saved him for me, so I came with a full heart to carry on my husband’s legacy,” she said. “The military molded him—he was the most loving man—that was Ed Ramsey.”

In noting his death, the Los Angeles Times quoted his statement to a reporter in 2001. “I look back and think of myself as a soldier, not as a hero,” Ramsey said. “I just had a temperament that made it impossible for me to surrender.”

Learn more online

For more information on Ed Ramsey or the film, visit edwinpriceramsey.com.