DAV member became America’s first Black female military pilot in 1978

Marcella Ng had never considered military service before an official with Army ROTC called. Known for being a tomboy and having an unquenchable thirst for the outdoors, Ng was persuaded to take a leap of faith by accepting an ROTC scholarship to the University of Wisconsin–Madison.

Little did she know that unexpected phone call would set her on a path to become the nation’s first Black female military pilot—a path that was not without struggle.

A native of central Missouri, Ng found her footing in college and enjoyed the regimented structure ROTC entailed. She also found success and was just one of two women chosen to be part of the all-service ROTC drill team on campus.

“We’d take the 1903 Springfield rifles, and we would flip them with bayonets on,” recalled Ng, who is a DAV lifetime member of Chapter 29 in Harker Heights, Texas. “Just being part of that was such a special thing.”

But it was the more physical aspect of training that sold her on a future in the Army.

“I had instructors that didn’t try to put limits on you—that was so important.”

Like her choice to join the Army in the first place, Ng had also never dreamed of flying. That changed in the summer of 1977 when an Army lieutenant colonel and pilot singled Ng out and encouraged her to earn her wings. After graduating the following year, 2nd Lt. Ng went to Fort Rucker, Alabama, to make history.

Ng was both the first woman and the first African American officer assigned to her first unit in Germany. But maintaining flight status proved nearly impossible. When other officers declined to assess her piloting abilities properly, uncertainty clouded her aviation career.

Officials organized two flight boards to determine if she could keep flying. The first was thrown out, according to Ng, over the impression of undue influence. A second board was held, and the members determined she should no longer fly. Ng ended up serving as the unit’s dining facility officer.

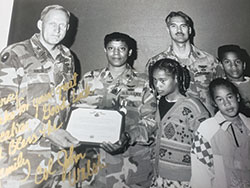

Despite the setback, Ng continued to climb the ranks as a transportation officer. Later in her career, while Ng was assigned to the 7th Infantry Division, a senior officer recognized her and informed her that discrimination had, indeed, played a factor in stripping her of her flight status.

“It was a club called ‘No Blacks, No Bra,’” said Ng, referring to apparent prejudice against both her race and gender.

Despite unfair treatment at the beginning of her career, Ng remains proud of her service. She retired in 2000 at the rank of lieutenant colonel and having commanded a transportation battalion.

Today, Ng remains a pioneer, helping to pave the way for a new era in military aviation. She stresses to others the importance of not letting the negative occurrences influence their outlook.

“That’s the challenge, to keep telling young people, and especially young ladies, don’t let the circumstances of where you are, regardless of how rough it was, regardless of how bad it was, define who you are,” Ng said in a previous interview. “Because that’s not who you are.”

“Marcella is an inspiration to her fellow DAV members. In spite of the challenges she faced and the racism and sexism that held her back in her military career, she broke barriers and served with distinction,” said DAV National Commander Andy Marshall. “We’re grateful she continues to look out for her fellow veterans as a DAV life member, and it’s an honor to count her among our ranks.”

Air Force Maj. Kristi Buczek, a student at Maxwell Air Force Base’s Air University in Alabama, recalled Ng’s modesty even as she, unintentionally, helped to usher military aviation into a new chapter.

“She just saw herself as another person trying to make it through this difficult training and giving her all,” Buczek said in an interview in April. “And it didn’t dawn on her until other factors—other people pointed things out or maybe she got a little recognition—that she was unique and she really was paving the way for people.”